Capitalism: The Individualist Social System

#6 in a series of Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (2nd Expanded Edition)

Note to readers: I’m spending this weekend on recording the audio version of the book. It should be available within a month or so. This week’s serial is getting into the meat of the book with an introduction of Capitalism. Next week, I’ll be back with a new article, most likely on the the unwillingness of both the political left and right to seriously address the looming Social Security financial crisis in the light of the SECURE Act 2.0 making its way through congress. Until then, enjoy today’s article and have a wonderful week—and don’t forget to buy and rate/review the book.

5. CAPITALISM: THE INDIVIDUALIST SOCIAL SYSTEM

Throughout human history, collectivism has been the dominant force. Back in the hunter-gatherer tribal days, safety was in the group. The tribe had its “intellectuals”—elders, witch doctors, shamans, druids, and medicine men—who tried to make sense of a life that was poor, nasty, brutish, and short. The tribal chief was almost always a competent hunter or warrior who could organize both hunts and the defense against wild animals and other tribes. Individuals subordinated themselves to the tribe, because life on the outside meant certain death.

As humanity developed agriculture and settled down, forming villages, towns, and cities that organized into provinces, countries, and empires, the tribal ways stayed with us. As cultures evolved, tribal elders, witch doctors, medicine men, shamans, and druids became rabbis, priests, and mullahs. And to organize and defend the geographical area, tribal chiefs became local lords, kings, and emperors. The threats were variations on the same “life is poor, nasty, brutish, and short” theme from back in the hunter-gatherer days. Disease, injury, and war were constant companions, and few questioned the supremacy of the collective, of the now-larger tribe, over the individual.

However, individualism existed along with the collectivist tribal ways. Human nature was the same back then as it is today. Individual men and women had to think to survive and act on their thinking to get something accomplished, even if for the good of the tribe. The tribe didn’t have a Borg-like collective consciousness that assimilated the thoughts of its members. But, due largely to the severity of external threats, the individual took a backseat to the collective.

As civilization developed, philosophers and political thinkers tried to find methods in the madness. Around 2,500 years ago, Ancient Greece experimented with both democracy (Athens) and dictatorship (Sparta, Macedonia, and others). And the Roman republic and empire maintained elaborate political structures for nearly a millennium. Italian republics flourished in the late Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, with Venice surviving until Napoleon conquered it in 1797. And England got its Magna Carta in 1215 that introduced checks and balances between the king and the aristocracy. These systems, even if better than what came before in certain respects, took collectivism as a given, implemented statist social systems to organize society, and accepted the alleged right of some group to violate the rights of the individual in the name of God, king, or country. Nobody thought fundamentally outside the collectivist-statist box.

Not until the second half of the 17th century did English philosopher John Locke put the individual and individual rights on the socio-political map in earnest. And it was not until the late 18th century that a country made individual rights the justification for its founding and existence. That country was the United States of America. And, to this day, it is the only country with such a foundation, although there have been many more or less successful copycats around the world.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence advocated respect for and protection of individual rights—our inalienable right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness—and the U.S. Constitution codified these principles into law with its checks and balances to limit collectives and groups from using government power to their advantage. This system enabled many individuals to act on their thinking and to be in control of their lives on a hitherto unprecedented scale, as they were subject to a minimum of taxation, redistribution, and regulation. In important respects, the role of government was close to what we discussed in chapter 3, limited to protecting citizens from foreign aggressors (the military) and from domestic aggression (law enforcement), and to prosecuting domestic aggressors and settling disputes (the court system).

The American system unleashed a period of unparalleled progress that the U.S., along with other countries that adopted similar socio-political ideas, experienced starting in the 19th century.

But collectivism never went away completely. People held as slaves suffered brutal oppression, and women suffered various rights violations. But while these rights violations were eventually addressed, collectivism slowly seeped back into the system and weakened the checks and balances that were put in place to protect our individual rights. In the late 19th and early 20th century the pace picked up in important respects. The collectivist advocacy for violating individual rights in the name of “the common good,” “the public interest,” “the will of the people,” “the will of the majority,” or “minority interests” gave us government (public) education, Social Security, Medicare, a plethora of other programs, and the regulatory state. Slowly but surely, welfare statism became the social system of America that we live with today.

You may wonder why this historical overview is included in a citizen guide. It is important as context when we look at why capitalism is the only social system compatible with individualism, and why it is the only social system that consistently protects individual rights. History helps us understand why capitalism is misunderstood and misrepresented and why it is ignored or rejected by so many.

As illustrated by this history, individualism as a political ideology and its social system ally capitalism represent a break with thousands of years of collectivist and statist traditions. If we represent 6000 years of organized civilization as a year, John Locke appears on the scene around December 10, and the United States is founded a week later. If we extend the timeline, admittedly somewhat arbitrarily, to 100,000 years of semi-organized tribal life, Locke’s Two Treatises on Government is published in the afternoon of December 30, and the United States is founded just before dawn on New Year’s Eve. In this perspective, the discoveries of individualism and capitalism have just appeared on the scene. It is not surprising that they are misunderstood, looked upon as a threat to the age-old collectivist/statist dominance, and met with resistance.

Furthermore, as we will see shortly, capitalism as a social system has so far not been consistently implemented anywhere. This means that champions of the proposed new capitalist system have few comprehensive concretes to point to, while detractors find ammunition in an abundance of failed welfare statist experiments that they (falsely) blame on capitalism.

5.1 What Is Capitalism?

Capitalism is commonly viewed as a free market economic system. However, as a social system it is so much more. It is the only social system that recognizes that individual rights are the only true rights and that the only role of government is to protect those rights. Under capitalism all property is privately owned and privately controlled (except perhaps some property used for appropriate government functions). Any alleged “rights” of a collective or a group in the name of “the common good,” “the public interest,” “the will of the people,” “the will of the majority,” or “minority interests” are incompatible with capitalism.

Capitalism is the only social system that fully recognizes that you are in control. Only in a capitalist social system are you completely free from statist interference in making the life choices listed at the beginning of the book. You decide, within the context of voluntary interactions with others, your career, your education, your job, your romantic partner, your friends, your family interactions, your family planning, your children’s education, your place of residence, what you eat and drink, your healthcare choices, what other products and services you consume, what causes you support, how you spend or save the money that may be left at the end of the month, when to retire, how you save for retirement, and what should be done with your life’s belongings when it’s time to check out. Capitalism acknowledges and respects that you have the individual rights to be in control of your life.

As a social system, capitalism also demands that you respect that others have the same right to be in control of their life. Capitalism rejects the notion that something is so important it should be provided for free, or be subsidized or regulated, by the government. And if you violate someone else’s individual rights by fraud, theft, or worse, the very limited government steps in to meter out justice by requiring that you compensate the victim financially, or by sentencing you to a term in prison or the like.

Capitalism recognizes that we properly interact by engaging in voluntarily trade. We sell our skills to employers in exchange for a salary or wage, we buy goods and services from sellers, and we trade non-material values when establishing friendships and romantic relationships. If you have something I value, and I provide something of value to you, let’s be business associates or friends or lovers. And if we can’t come to terms—if the pay is too low, if the skillset is not a match, if the price is too high or the quality too low, or if the relationship changes over time diminishing its value—we are free to go our separate ways as long as our individual rights aren’t violated through a breach of contract or worse.

In economics, the term laissez-faire capitalism is sometimes used to differentiate “unrestricted” capitalism from welfare statism, which has a mixed economy with elements of capitalism. Laissez-faire is derived from the French expression “laissez-nous faire” which roughly translates to “let us be” (this time a worthy French import). It means that individuals are left to be in control of their lives and the government plays a very limited role in society. But since we’ve already defined welfare statism as a social system mixing both protection and violation of individual rights, we’re using the word capitalism without any qualifiers to represent the only social system compatible with individualism.

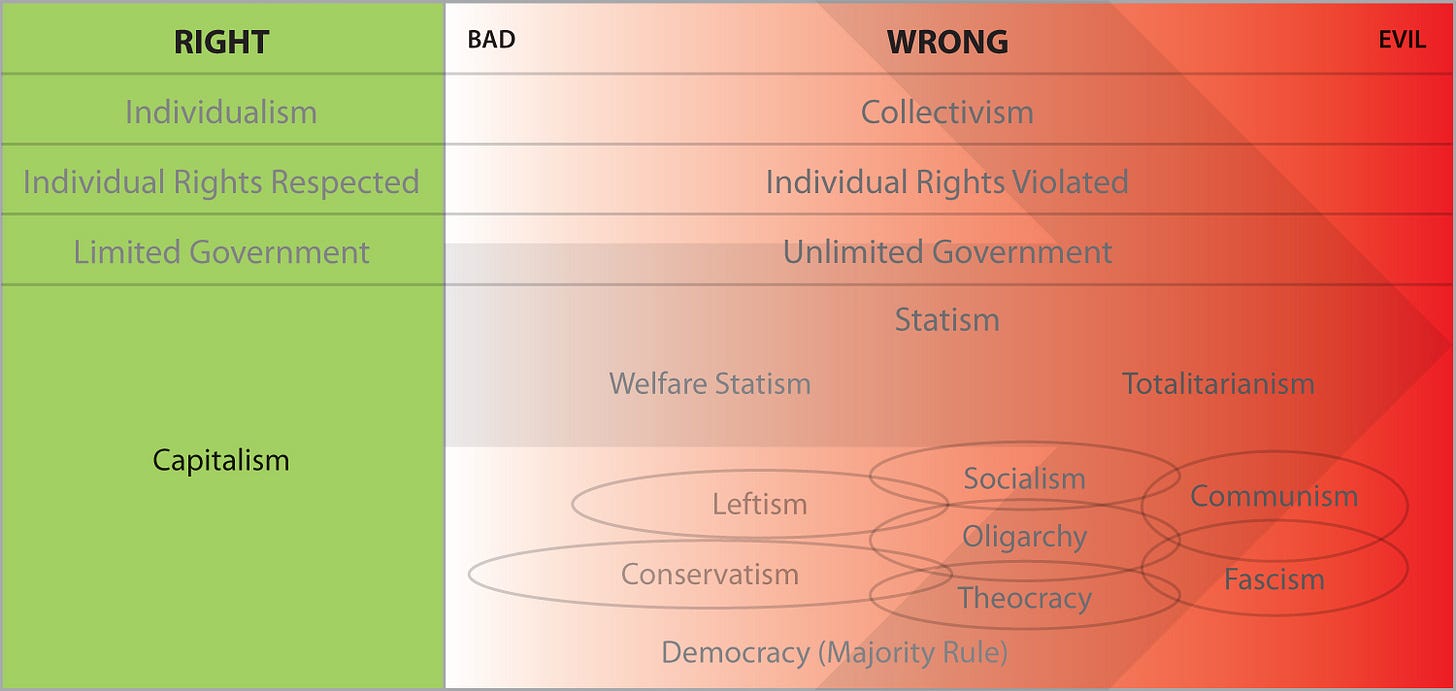

Here’s our illustration with capitalism added as the last piece of the morally Right or Wrong puzzle:

© 2022 Anders Ingemarson; from “Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (2nd expanded edition)”

Note that capitalism doesn’t come in degrees like statism does. Even the slightest sanctioned violation of individual rights in the name of the collective or group puts a social system on the morally Wrong side. It may be to the very left in the gray box as a very mild form of welfare statism, but it is nevertheless Wrong. It is not capitalism.

It is challenging to envision what a capitalist social system looks like in practice because we have yet to see one consistently implemented. The closest we’ve come is in the United States during a brief period after the Civil War, and only in some of the northern states. But statism was by no means absent during this period so we cannot point to it as an example of consistently implemented capitalism.

The best example available to us today is the information and digital revolutions of the past 50 years. In general, the period from 1970 to 2020 has seen welfare statism slowly growing more entrenched in the United States. However, information and digital technology has remained largely free and therefore prosperous. The individual rights of innovators and entrepreneurs have been less violated by regulation in these sectors than elsewhere. Producers in this field have had more freedom to put their thoughts into action without government interference than have people in any other area of society. The absence of regulation has allowed them to keep up the high pace of innovation—no need to wait for government approval before charging ahead—and contributed to extraordinary profits, which for the most part they have reinvested in their businesses.

The results have been spectacular both in the information and digital technology sectors and in the many other industries that have benefitted from adopting the advances of this revolution. And recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the fruits of this semi-capitalist sector significantly lessened the hardships. Yes, millions were unemployed for a period of time, and many small and medium sized businesses were crushed. But imagine how much worse life would have been without the digital revolution allowing for working from home, online shopping, Amazon delivery, Google searches, Zoom conferencing, Netflix streaming, telehealth, and countless other blessings. As a result, now more than ever, this close-to-capitalist “enclave” sustains the rest of society and cushions the blow of the increasing welfare statist influences.

But the information and digital revolutions have not been completely unaffected by welfare statism. For example, Microsoft was accused of violating welfare statist antitrust laws at the end of the 1990s (more about antitrust later). This was not an isolated incident; the antitrust cloud hangs permanently over this and every other industry in a welfare-statist society. Get too big and you get in trouble as manifested by bipartisan threats to regulate the internet and break up some of the big technology companies. And often your competition, quietly or vocally, cheers on the government to take you to court.

To take another example, cities in the U.S and around the world put up statist regulatory barriers to prevent Uber and Lyft from competing with local public transportation and taxi monopolies. Cities often also restrict Airbnb from making inroads in the hospitality industry. And taxing authorities large and small cash in on online sales, cheered on by brick-and-mortar retailers who fear the competition.

Given what you probably learned in school or hear in the media about capitalism, you may have a hard time recognizing capitalism as the social system of freedom and prosperity—the social system that protects, not violates, your individual rights. Before the objections pile up too high, let’s cover some of the virtues of capitalism and set straight a few misconceptions in the process.

In coming sections, we will explore why, under capitalism,

cronyism vanishes,

monopolies are short-lived,

political inequality is eliminated,

envy is politically impotent,

unimagined advances are unleashed,

safety nets flourish,

the unfortunate and underprivileged are empowered,

recessions are few and mild,

K–12 education is affordable and of high quality,

housing is affordable,

few need a college education,

inflation is eliminated,

the world is peaceful,

the impact of natural disasters such as pandemics is reduced,

taxes are in the past,

infrastructure investments are optimized,

immigration is an opportunity, not a threat,

the environment gets the real deal, and

racism and prejudice are relegated to the fringes of society.