A Brief History of Left and Right, Individualism and Collectivism: Who Has Rights?, and The Role of Government

#3 in a series of Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (2nd Expanded Edition)

Note to readers: This is the third installment of “Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (2nd Expanded Edition) to be published on Independence Day. I’ll pause the serial next week for an article about the anti-human-flourishing complex.

10/30/2024 updated to reflect content of the 3rd expanded edition.

1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF LEFT AND RIGHT

The political terms “left” and “right” have been with us since the French revolution in the late 18th century when members of the French National Assembly divided into supporters of the king to the president’s right and supporters of the revolution to his left.1 Those siding with the king favored the status quo, preserving the existing royal, aristocratic, and clergy power structures, while those siding with the revolution advocated for more power to the people.

The popularity of the terms waxed and waned over the next 150 years, and it was not until the 1960s that they became firmly established in the American political vocabulary. In the United States today, the right is represented by conservatives—classical liberal, fiscal, social, compassionate, traditional, nationalist, etc.—and the left by center leftists, social liberals, social democrats, progressives, democratic socialists, and others.

The French are famous for their contributions to the sciences, the fine and culinary arts, and fashion. However, political inventions coming out of France have often done more harm than good. The French-derived representation of politics on a spectrum from left to right is a good example, as it has caused much confusion. As we will see in future chapters, if the standard is that you should be in control of your life, the political left-to-right spectrum presents us with two fundamentally morally Wrong alternatives while dispensing with the only morally Right choice. Because neither the political right nor the left puts you and your rights center stage.

2. INDIVIDUALISM AND COLLECTIVISM: WHO HAS RIGHTS?

Contrary to the commonly accepted views, today’s political left and right are not opposites but, in fundamental respects, two versions of the same political ideology: Collectivism.

Collectivism, or “group-ism”, claims that your life and work belong to some collective or group. It holds that the collective may dispose of you in any way it pleases for the sake of whatever it deems the good of the group in question. Depending on the version of collectivism, that group may be a nation, race, faith, class, sex, gender, tribe, caste, gang, family, majority, minority, or some other classification.

Under collectivism, your individual rights are sacrificed for the alleged benefit of the group. Terms such as the “common good,” “public interest,” “will of the people,” “will of the majority,” or “minority interests” often are used to justify the subordination of the individual to the group.

The political right often is associated with collectives such as the nation, religious groups, and family, while the political left leans toward viewing people fundamentally as members of their race, class, sex or gender. Although each holds different groups as most important, both hold that your individual rights must be subordinated to the group.

The antidote to collectivism is individualism, which says that you are an independent, sovereign person who fundamentally has one right: the right to your own life. Individualism holds that the right to your own life is an expression of your nature as a thinking human being. As mentioned in the prologue, nobody else can do your thinking for you, and therefore you should be free to act on your thoughts to sustain, further, and enjoy your life, while respecting that others have the same right.

From the right to your own life follows a number of derivative rights, including but not limited to: the right to liberty, because you have to be free in order to act on your thinking; the right to freely trade with others, if you think that such action is of benefit to you and the other party consents to the trade; and the right to property, that is, to the fruits of your labors. Taken together, these constitute your individual rights.

In contrast to collectivism, individualism holds that individual rights are the only rights, and that a group or collective cannot have any rights apart from the individual rights of its members.

Belonging to or identifying with groups obviously has many benefits. Rooting for your local or college sports team, getting professional satisfaction from belonging to a team at work or being member of a union, or meeting with fellow immigrants to celebrate traditions from the home country, can offer many rewards. And most of us get tremendous value from the support and friendship of a loving family. Depending on our individual interests, we form professional groups and volunteer groups and join churches, bridge and book clubs, real and fantasy sports leagues, and crocheting circles. If your imagination runs dry, just check out Meetup for the numerous ways we can enjoy each other’s company. There is certainly a “groupie” side to most of us.

But according to individualism, belonging to a group must be voluntary. Membership must not violate your individual rights. It requires the freedom to join or leave the group according to what you deem in your best interest. If your team at work or your union doesn’t add anything professionally, if those home country traditions start to feel stale, if your family demands that you join the family business instead of pursuing your true passion, you’re free to say “thanks, but no thanks” and distance yourself from or leave the group in question.

Collectivism, on the other hand, claims that you should continue to belong to the union because “there is strength in numbers,” continue to celebrate the traditions of the home country because of “a common heritage,” and give in to the family demands because “family comes first,” or “blood is thicker than water.”

In the realm of politics, collectivism claims the right to override your individual rights for the benefit of the group. Individualism, on the other hand, rejects this notion that your life must be subordinated to the group in favor of respecting your individual right to voluntarily associate with others as you best see fit.

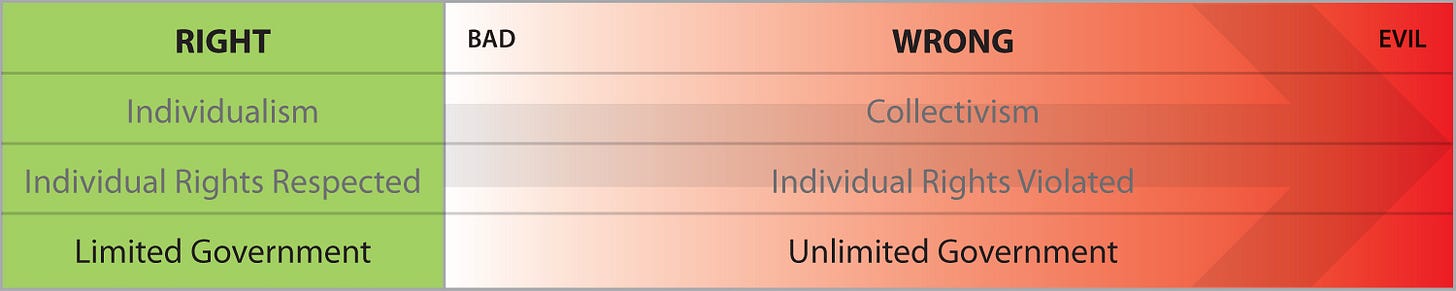

We can illustrate the discussion so far as follows:

© 2024 Anders Ingemarson; from “Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (3rd expanded edition)”

The premise of this guide is that you have the individual right to be in control of your life, that individualism is morally Right (upper case “R”) and collectivism is morally Wrong (upper case “W”). You may notice that collectivism exists on a spectrum from bad to evil (indicated by the shaded arrow in the “WRONG” column) as your individual rights may be less or more violated. But by the standard of individualism, individual rights violations are morally Wrong, regardless how minor they are (illustrated by the absence of an arrow in the “RIGHT” column). The width of the columns is not an indication of their relative importance, but a consequence of the fact that we unfortunately have more to illustrate that is morally Wrong than morally Right as we continue the discussion.

The single most important factor for being in control of your life is that your individual rights are respected and protected. Much of this book focuses on why that is the case and what you can do to champion individual rights with your activism, if you’re so inclined, and with your vote. Next, let’s look at where the government comes in, because it does indeed have a role to play.

3. THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

If the single most important factor for being in control of your life is that your individual rights are respected and protected, then you would want someone to deter others from initiating physical force against you. And conversely, you would have to accept that that someone will deter you from initiating physical force against others as well; it goes both ways. Physical force in this context does not mean bodily harm only; it comes in many forms of individual rights violations from libel, embezzlement, forgery, fraud, and breach of contract to theft, battery/assault, and homicide.

If physical force is to be barred from social relationships, we need an institution charged with the task of protecting our rights under certain rules of social conduct. Government is that institution, and the rules of social conduct are what we call “the rule of law.”

Properly defined, “A government is the means of placing the retaliatory use of physical force under objective control—i.e., under objectively defined laws.” It is a precise but admittedly rather dense definition, so let’s break it down.

“Retaliatory use of physical force” means simply the force applied for breaking a law that is in place to protect our individual rights. If you break the law, you’ve got to pay one way or another. Retaliatory use of physical force may come on a spectrum from requiring financial compensation to imposing life in prison and death depending on how serious the rights violation is.

“Objective” (as in “under objective control”) means that the rules of social conduct—the law—should only address violations of individual rights. And the rules should specify the proper level of retaliatory physical force for breaking them. Nothing more, nothing less.

How do we go about achieving this? We, the governed, that is, you and I and everybody else, consent to give the government the monopoly on the use of physical force (excepting self-defense in emergencies). Why? To prevent individuals and groups from exercising their own, possibly competing, views of what should be the rules of social conduct and their enforcement. Without our consent—without giving the government the monopoly on the use of physical force—society would descend into anarchy. But properly implemented as outlined above, government is a necessary good that we don’t want to be without. Properly implemented, government is morally Right.

But individualism and collectivism have vastly different views of the role of government. Individualism recognizes your right to be in control of your life and therefore acknowledges only a very limited role of government. According to individualism, government exists for one reason only: to protect your individual rights from being violated by others. In other words, individualism demands that government be implemented according to the definition discussed above: “A government is the means of placing the retaliatory use of physical force under objective control—i.e., under objectively defined laws.”

A truly limited government has three functions. It uses its monopoly on physical force to (1) protect you from foreign aggressors (the role of the military), to (2) protect you from domestic aggression such as fraud, theft, murder, etc. (the role of law enforcement), and to (3) prosecute domestic aggressors and settle disputes (the role of the court system).

Collectivism, on the other hand, sees government force as a tool to further the goals of the group or groups of choice through taxation, redistribution, and regulation. Because collectivism considers your individual rights subordinated to the alleged rights of the collective or group, government in a collectivist society is more or less unlimited. By that we mean it can use more or less physical force, depending on how consistently a particular collectivist vision is implemented.

Under collectivism, the law expands to treat actions and behavior that don’t violate individual rights as offenses punishable by law (criminal or civil). A collectivist government imposes rights violations on a range from relatively minor, such as zoning laws, food regulations and excise taxes, to major, such as anti-trust laws and government takeover of entire sectors of society, for example large parts of healthcare and education (much more about this in later chapters). As government strays from its core role of protecting individual rights, the law becomes non-objective. And government goes from not only being the protector but also a violator of individual rights, expanding its monopoly on retaliatory physical force to enforce the non-objective laws. For example, government punishes those found guilty of breaking anti-trust laws, of not complying with food regulations, of avoiding excise taxes, and of daring to compete with the government-controlled areas of healthcare and education (again, later chapters will discuss these and other examples in much more detail). Under collectivism, government becomes morally Wrong: an instrument for those who want your individual rights to take a backseat to the alleged group rights.

Adding the role of government to our table gives us the following picture:

© 2024 Anders Ingemarson; from “Think Right or Wrong, Not Left or Right: A 21st Century Citizen Guide (3rd expanded edition)”

Limited government is morally Right and unlimited government, regardless of size and reach, is morally Wrong. You are correct if you think this description of a limited government is far from the government we have today. We are positioned on the unlimited government spectrum, but where? We’ll answer the question in the next chapter after we have looked at how collectivism manifests itself in society.